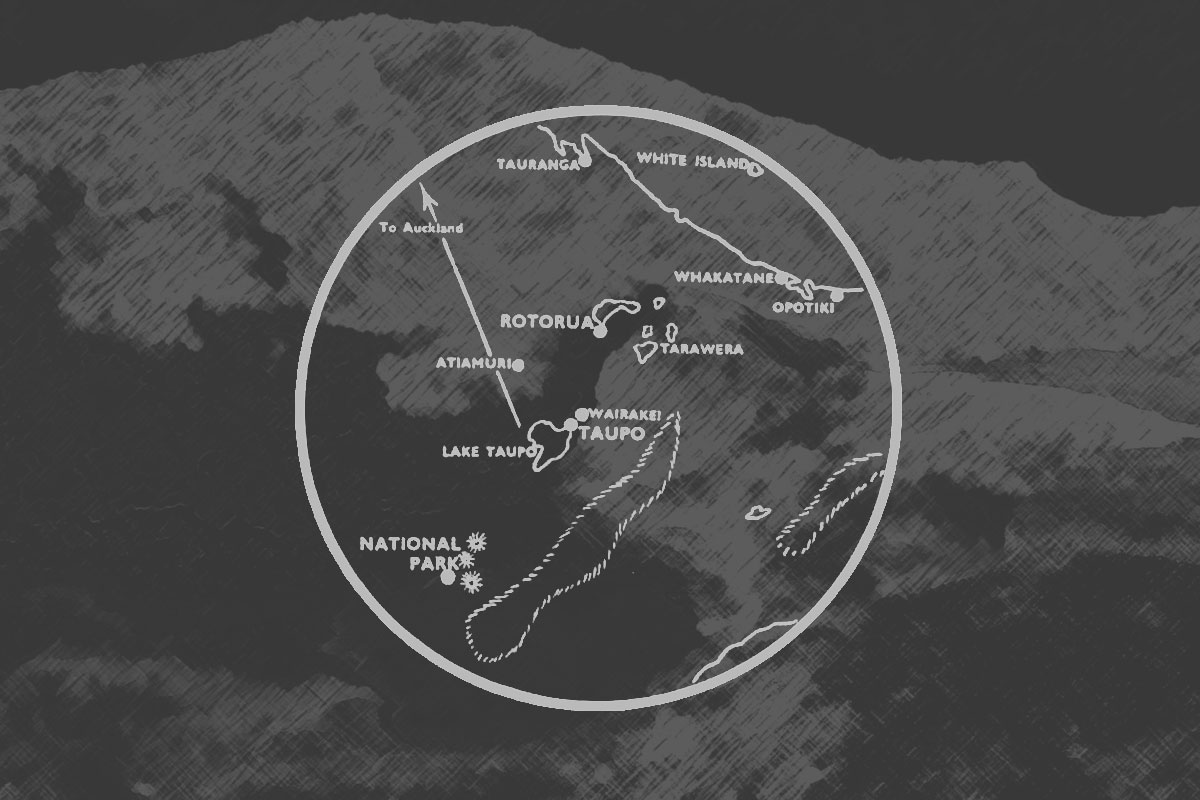

The inner crater lake in Whakaari/White Island volcano, photographed in November 2011. Photo: Javier Sánchez Portero, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Richard Wong She is one of New Zealand’s leading plastic and reconstructive surgeons, specialising in burns. As the clinical leader for burns at the New Zealand National Burn Centre, he and his team led the healthcare response to the Whakaari/White Island volcanic explosion in 2019.

Compared with the usual 5 to 10 per cent survival rate from a volcanic eruption of this sort, the ultimate survival rate following the Whakaari explosion was about 53 per cent.

Dr Wong She was scheduled to present on the response at the recent ANMF (Vic Branch) Australian Nurses and Midwives Conference, but unfortunately he was recalled. Instead, he prepared a well-received pre-recorded presentation, summarised below.

Five key reflections

Dr Wong She offered five key reflections:

- Don’t complain about how bad things are now – they can get worse.

- The five Ps of surgical learning – proper planning and preparation prevents problems – should also include practice.

- No plan survives first contact intact, but the best plans are adaptable, need less changing, and can also be applicable to other unexpected situations and disaster settings.

- People are more important than processes or plans.

- Communication is key.

Don’t complain about how bad things are now – they can get worse

On 9 December 2019 when the volcano erupted, there were 47 tourists on the island. Thirteen were declared dead or missing that day, leaving 34 injured to be triaged and treated by Dr Wong She and his team.

In the weeks prior, this team had been operating at almost double capacity, and that workload had already taken a huge toll. ‘I was concerned that my colleagues were about to leave for Christmas, and I wasn’t sure how I was going to cope. The solution from management was the equivalent of: “there there”.’

Of course, things were about to get worse.

Amid the initial chaos and confusion, the team learned that the volcanic ash contained hydrofluoric acid, which can cause significant and fatal hypocalcemia. ‘You only need a two per cent burn size to be lethal,’ Dr Wong She explained, ‘and the average burn size of these patients was close to 50 per cent.’

This meant that instead of just cleaning and performing escharotomies, there was an urgent need to physically remove all of the burned tissue. To put things in perspective, Dr Wong She said that ‘on the first full day [following the eruption], we did essentially a week’s worth of operating. By the end of the first week, we had done a month’s worth of operating. Ultimately, we did the equivalent of six months of work in three months – on top of the existing work that we had.’

Proper planning and preparation prevents problems

The 9th of December was registrar changeover day in the National Burn Service, which meant the team that would end up responding to the Whakaari disaster were all new. This turned out to be ‘a blessing in disguise’, as the registrars had all been recently trained in burn care thanks to planning Dr Wong She had put in place while on the Board of Plastic Surgery Training, which mandated a rotation at the service.

‘They used their training exceptionally well. I also applaud my colleagues, who were humble enough to say to their registrars: you’ve had more recent training in this; you tell me what I need to do, and we’ll do it.’

Something they discovered early on was proper planning and preparation are not enough to prevent problems; you have to also practise. ‘It’s all very well simulating the management of one patient but simulating the management of multiple patients concurrently really highlights if there are any glitches in your system, especially if multiple services need to be involved.’

No plan survives first contact intact

Not all of Dr Wong’s She’s planning worked out.

In 2010, he and two colleagues wrote a burn disaster management plan. Unfortunately, they didn’t predict this particular disaster ‘at all well’. The plan was based predominantly on thermal, chemical and electrical burns, and didn’t take into account the technical challenges of volcanic burns.

It was also based on burn size, but not all parts of your body are equal. ‘Every one of the Whakaari patients had severe hand burns. A hand is only one per cent but when both sides are affected, it takes an inordinate amount of time to successfully debride, compared to one per cent on your back or your thigh.’

In the middle of the disaster, there were not enough skilled personnel available. They ran out of equipment, and resources. There were other logistical constraints that hadn’t been predicted. ‘For example, these patients all ended up with unique microorganisms, which necessitated them being the last patient on our list so that the theatre could be decontaminated. But when four patients have to be the last on your list, it makes things tricky.’

People are more important than processes or plans

‘The thing I really want to stress,’ Dr Wong She said, ‘is that care was ultimately directed by need and not constrained by a model. People are far more important than processes or plans. Forget about leadership; what you actually want are active followers: people who are adaptable, flexible, resourceful.’

This requires networking, friends and contacts, he added. ‘We leveraged all the contacts we had made during meetings and conferences, and I would strongly recommend that at the meetings and conferences you attend, you make connections.’

Communication is key

Communication was critical, but very difficult. They needed accurate, up-to-date information in an environment where the information was changing rapidly. They needed to know who could provide the information, and who else needed it. And they needed to get the information disseminated quickly.

Privacy and confidentially meant many of the standard tools that might be used to disseminate information were out of the question. ‘I guess one thing to be thankful for from COVID,’ Dr Wong She deadpanned, ‘is that the ability to have teleconferences and to share information contemporaneously is a lot easier than it used to be.’

What can we learn from all of this?

Concluding, Dr Wong She highlighted the positives in his key learnings:

- Don’t complain about how things are now; change them, make them better.

- Plans are best made yesterday but the next best day is today; don’t forget to practice them.

- No plan survives first contact but if COVID has taught us anything it’s to pivot, shift and be agile.